PART II THE HUMANITARIAN LANDSCAPE

Photo: © Norwegian Church Aid/Håvard Bjelland

Chapter 2 The global humanitarian situation

2.1 Complex crises result in increased humanitarian needs

Humanitarian needs have increased drastically in the five years since the previous strategy was launched. The number of people in need of humanitarian aid has more than doubled, from 135 million in 2018 to more than 300 million people in 2024.3,4

Both sudden-onset and protracted crises have become more complex. Crises are also affecting entirely new countries. They are caused by new and recurring armed conflicts, climate change, increasing polarisation, the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic, geopolitical upheavals, democratic decline, and poverty.5 Increasing urbanisation entails that crises impact a greater number of people when they occur.

Most crises are protracted in nature, and the vast majority of people in need live in countries that have had a UN-coordinated appeal for five or more consecutive years.6 Many people are experiencing multiple crises simultaneously. Conflict affected areas are also often the most vulnerable to climate change and natural disasters and the least able to handle them.

At the same time, it has become more challenging for humanitarian organisations to reach those in need of assistance due to security challenges and bureaucratic hurdles. Armed actors make it particularly difficult to gain safe access to those in need.7

Protection needs in humanitarian crises are substantial and growing. Populations are also severely affected because their fundamental rights are not respected, and they are subjected to violence and abuse. Marginalised groups and children are particularly vulnerable.

Sexual and gender-based violence is a widespread problem in crisis and conflict situations. Human trafficking is also a major problem in many crises.

Armed conflicts are increasing in number and duration, causing massive humanitarian needs. The number of both armed conflicts between states and armed conflicts involving non-state actors has increased. Wars are often being fought in cities and other densely populated areas. Sieges and blockades are often used as strategies by parties to armed conflict. This results in many civilians being killed or injured and causes large-scale displacement. When explosive weapons are used in populated areas, it is estimated that nine out of ten victims are civilians.8 Approximately one in five children in the world lives in a conflict area or is displaced by war.9 The number of children killed or injured due to armed conflict is very high.

A growing number of people are forced to flee their homes. According to the UNHCR, the number of displacedpeople was more than 110 million at the end of 2023.10 Furthermore, the UNHCR expects that there will be more than 130 million forcibly displaced people by the end of 2024.11 This is 60 million more than at the end of 2018. More than two-thirds are internally displaced. Most people who flee their home country seek refuge in neighbouring countries, which often have limited capacity to meet the needs of both displaced people and their own population.

Vital infrastructure is destroyed and often not rebuilt, as crises and conflicts persist. This devastation causes human suffering and can have major and long-lasting economic and social consequences.

The number of climate-related and natural disasters has increased significantly since 2018. The world’s population is experiencing more frequent droughts, floods, wildfires, and landslides, triggering new humanitarian needs. Climate phenomena, such as El Niño, are increasingly leading to droughts, floods, and extreme weather events. Climate change is an increasingly important cause of displacement according to the UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.12 Many communities are affected by several of these crises simultaneously.

A growing number of people are unable to secure enough food to feed themselves and their families. According to the World Food Programme (WFP), more than 300 million people in 72 countries are affected by hunger crises (IPC 3+)13,14 in 2024. These numbers are extremely high and are attributable not only to the aforementioned factors but also to structural poverty and inequality.

2.2 The structure of the humanitarian sector

The humanitarian sector includes international and local organisations with different mandates, competencies, and responsibilities. Norway engages with the UN-led humanitarian system, the International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement, the work of which is based on international humanitarian law, as well as the Norwegian humanitarian organisations and their local partners. These actors complement one another and cooperate through different structures, both globally and at country level.

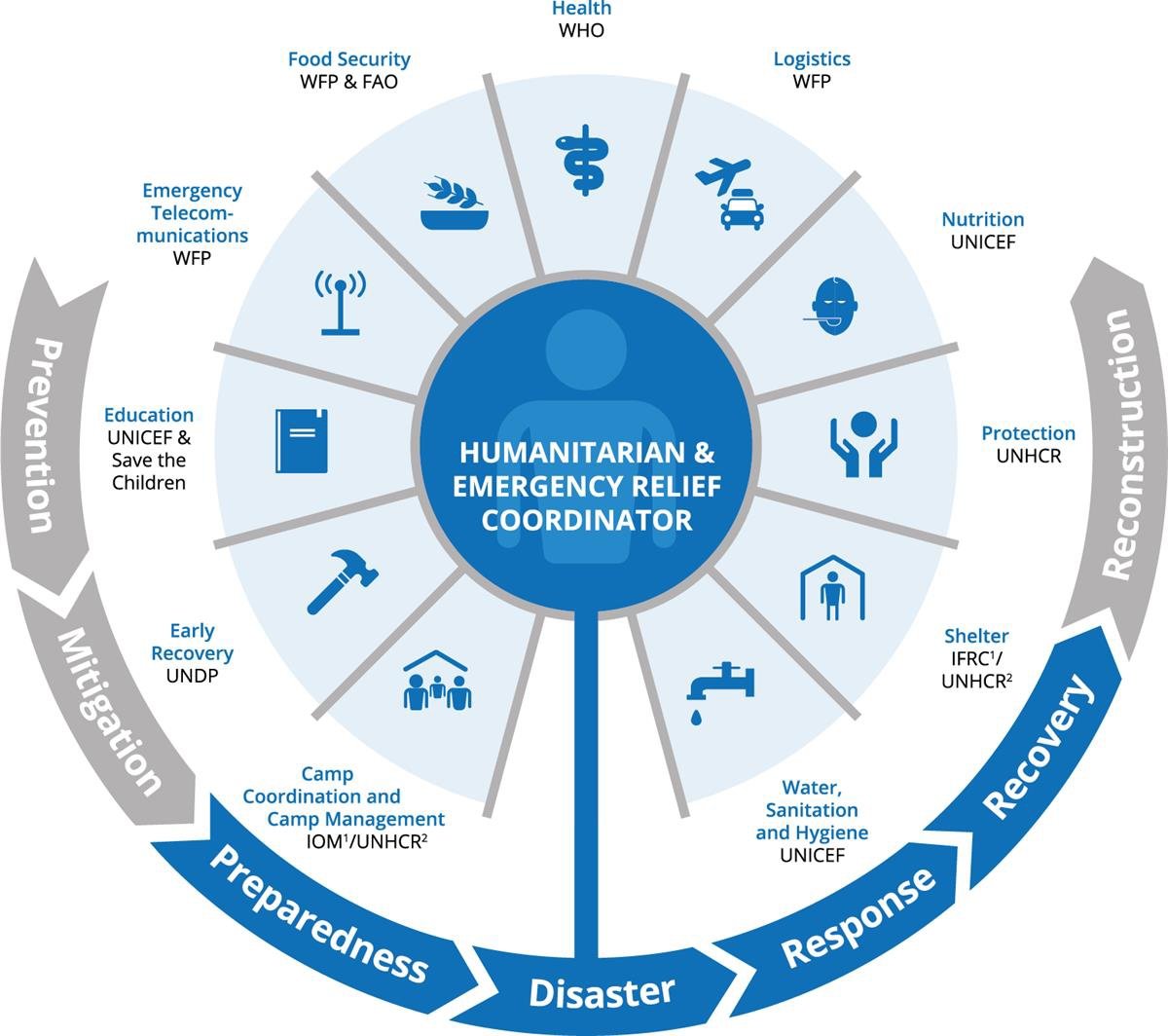

- Mandated by the UN General Assembly, the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) coordinates humanitarian efforts in crisis-affected countries through what is known as the cluster system, where each sector of humanitarian action has a UN organisation with a relevant mandate and competence as cluster coordinator. These clusters coordinate the efforts of local and international organisations. See Box 1.

- Mandated by the 1951 Refugee Convention and the UN General Assembly, the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) leads and coordinates the response in refugee host countries. The response in refugee host countries is organised into sectors, with the various UN organisations and other humanitarian organisations contributing their competencies and resources.

- The International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) has a separate mandate pursuant to the Geneva Conventions to protect and assist people who are victims of armed conflict, and operates independently of the UN system. It is part of the Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement, together with the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC) and more than 190 Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies. At the country level, the host National Society leads and coordinates the humanitarian response with support from ICRC in conflict situations, and with support from IFRC in other humanitarian crises, including natural disasters.

In addition, national and regional preparedness and response mechanisms have been established, which are activated particularly in connection with natural disasters and public health crises. Important contributions that Norway can draw upon in international humanitarian response are the Norwegian Directorate for Civil Protection (DSB) and the EU Civil Protection Mechanism (UCPM).

There have been several reforms to the UN humanitarian structure that have made it increasingly efficient and more capable of reaching large numbers of people. However, there is a common recognition that the structure needs to be further simplified and that the UN needs to work more closely with local actors. This is an ongoing effort led by OCHA.

Photo: © UNICEF/UN0372375/Ocon/AFP-Services

2.3 Humanitarianeffortsarechallenged

In recent years, the humanitarian sector has grown and become more professional and more effective. Humanitarian financing has increased, humanitarian actors are helping more people than ever before, and humanitarian efforts are better coordinated and achieve better results. However, the gap between needs and available resources is large and growing, and is expected to continue to widen in the years to come.

Humanitarian financing is often unpredictable and short-term, while humanitarian crises often have clear warning signs and tend to last for a long time. This makes long-term planning difficult for humanitarian actors.

The sector is also challenged by attempts to politicise humanitarian aid. Some organisations are perceived as Western-based and oriented, with limited connections to local communities. Local populations may have experiences from previous crises that generate a distrust of the international community which humanitarian actors are perceived as being part of. The legitimacy and relevance of the humanitarian sector are challenged when the response does not meet the needs of crisis-affected people, and neither the authorities, parties to conflicts nor the international community are able to resolve the crises.

Most often solutions to crises affecting populations are found outside the humanitarian sector. A comprehensive policy approach and the interaction of instruments within long-term development policy, conflict resolution and peace building, humanitarian efforts as well as climate action and human rights efforts are necessary.

The Sustainable Development Goals will not be achieved unless more is done to include people affected by crisis and conflict. Intensified and better coordinated efforts to reach the most vulnerable people are needed if we are to live up to the Leave No One Behind principle.15

Box 2.1 The humanitarian cluster system

The aim of the humanitarian cluster system is to ensure good coordination and avoid gaps and duplication in humanitarian response. The cluster system is activated in humanitarian crises at the request of the UN Emergency Relief Coordinator. The clusters are groups of humanitarian organisations, both UN organisations and non-governmental organisations, working in sectors such as water, health and protection. One or two organisations have dedicated leadership responsibility in each sector.

Figure 2.1 The humanitarian cluster system

1 Disaster situations

2 IDPs (from conflict)

Source: OCHA

Chapter 3 International humanitarian law and the humanitarian principles

International human rights law, the 1951 Refugee Convention and international humanitarian law form the legal framework for humanitarian action. Common to these rules is that they concern the protection of human lives and dignity. International humanitarian law only applies in situations of armed conflict, while international human rights law applies at all times, in peace and in war. It is crucial that humanitarian efforts are based on the rights enshrined in this legal framework. This rights-based approach also entails focus on participation, non-discrimination and accountability, in addition to the right to life, food, health services and education.

Under international humanitarian law, parties to armed conflict have a number of obligations based on the requirement to ensure balance between the military need to use armed force in certain situations (the principle of military necessity) and the need to prevent/limit to the greatest extent possible the harm and suffering inflicted as a result of use of armed force (the principle of humanity). This balance is reflected in the rules and principles of IHL, inter alia in the prohibition against directing attacks against the civilian population, the requirement that parties to an armed conflict must distinguish between civilians and combatants and between civilian objects and military objectives (the principle of distinction), as well as the prohibition against launching attacks expected to cause incidental loss of civilian life, injury to civilians, damage to civilian objects, or a combination thereof, which would be excessive in relation to the concrete and direct military advantage anticipated (principle of proportionality). International humanitarian law also contains several obligations to protect civilians and the wounded regardless of which side they are on, and to protect health workers and medical facilities, vital civilian infrastructure, as well as nature and the environment. Furthermore, parties to armed conflict must allow and facilitate the rapid and unimpeded passage of humanitarian relief.

Failure to respect and comply with these rules is a widespread problem in many armed conflicts, and the consequences for civilians are severe. This problem is exacerbated by the fact that many of today’s armed conflicts are taking place in densely populated areas.

Today, the constellation of actors involved in armed conflicts tends to be more fragmented than it was in the past, and it can be difficult to identify exactly who the parties to the conflict are at any given time. Armed groups, other non-state actors, terrorist organisations and criminal groups motivated by financial gain often do not relate to the rules of international law. In some cases, this may be due to a lack of knowledge of the rules. The educational efforts of the ICRC and other actors are therefore of great importance in promoting increased compliance with international law, including on the part of these groups. State actors also violate international law in many armed conflicts. Political will, in addition to knowledge, training and leadership in the armed forces, is key to ensure the protection of civilians. The development of new weapons technology, such as autonomous weapons, and the use of unconventional warfare, including cyberattacks, also add to the challenges regcompliance with the established rules of international humanitarian law.

Box 3.1 International humanitarian law

International humanitarian law consists of several international conventions as well as customary international law rules that have evolved over many years, and which are considered binding upon all. The four Geneva Conventions of 1949 have been universally ratified, and form, together with Additional Protocols I and II of 1977 the core of international humanitarian law. All parties to a conflict, including non-state armed groups, are bound by international humanitarian law. All states have a responsibility to respect, and to ensure respect for international humanitarian law.

Box 3.2 Sexual violence as a war crime

Sexual violence includes violations such as rape, sexual slavery and forced pregnancy. Conflict-related sexual violence is prohibited under international humanitarian law. Depending on the circumstances, sexual violence may be considered both as individual war crimes as well as crimes against humanity, and in certain situations it may also be considered a constituent act in the crime of genocide. Nevertheless, conflict-related sexual violence (CRSV) is often used as a method of warfare. CRSV is addressed in several UN Security Council resolutions on Women, Peace and Security (WPS).

Civilians and civilian infrastructure, such as hospitals and schools, are often attacked and it is becoming increasingly difficult to gain humanitarian access and provide protection.16,17,18

To ensure safe and unimpeded humanitarian access to civilians and promote respect for international humanitarian law, it is necessary to engage in dialogue with the various parties to conflict.

Compliance with international humanitarian law reduces civilian suffering, prevents war crimes, and can contribute to strengthening the possibility of various peace initiatives. Efforts to promote respect for international humanitarian law can thereby contribute to conflict resolution.

Norway’s humanitarian efforts are based on the humanitarian principles (see Box 3.3). These principles constitute an ethical framework and operational tool for humanitarian actors to reach those most affected. Particularly in conflict-related crises, these principles are important to ensure that those affected have access to emergency assistance and protection, without discrimination, and regardless of where they are in relation to the line of conflict. For the safety of humanitarian workers, it is also important that they remain impartial and are not used in support of the political or military objectives of one of the parties. In striving for a comprehensive response, it is important to factor in the need for humanitarian actors to work in accordance with the principles. This is particularly important where the authorities are party to a conflict.

Actors in the humanitarian sector may be put under pressure to follow political instructions from the parties in an armed conflict, from their own authorities and from donors. This can make it challenging for them to uphold the humanitarian principles. It can also undermine the general respect for the principles and reduce access to various groups in vulnerable situations. It is crucial to engage in close dialogue with partners on such dilemmas.

In recent years, several new actors, both donors and operational organisations, have emerged. These actors do not necessarily adhere to the UN-based framework for humanitarian assistance. It is important that the established organisations and donors stress knowledge of and respect for the humanitarian principles to these new actors.

Box 3.3 The humanitarian principles

The humanitarian principles are derived from the Fundamental Principles of the International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement and are enshrined in international humanitarian law. They are to form the basis for all humanitarian action in both conflict situations and natural disasters, as set out in UN General Assembly resolutions 46/182 and 58/114.

The four principles are as follows:

Humanity Human suffering must be addressed wherever it is found. The purpose of humanitarian action is to protect life and health and ensure respect for human beings.

Impartiality Humanitarian action must make no distinctions based on nationality, gender, ethnicity, religious belief, or political opinions.

Neutrality Humanitarian actors must not take sides in hostilities or engage in controversies of a political, ethnic, religious, or ideological nature.

Independence Humanitarian action must be autonomous of authorities’ and other parties’ political and military actions and objectives.

The principles of humanity and impartiality are to form the basis for all Norwegian humanitarian efforts. The principles of neutrality and independence are a means of gaining trust and access to provide protection and humanitarian assistance in an impartial manner. How the principles of neutrality and independence can best be complied with will depend on the context. It is precisely because there are not always simple answers to the challenges humanitarian organisations must face, that Norway is seeking to promote an experience-based approach aimed at ensuring that the humanitarian response can reach those who are most vulnerable.

The Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs has drawn up a guidance note in consultation with several Norwegian humanitarian organisations. The purpose of the guidance note is to enhance respect for and promote compliance with the humanitarian principles. The guidance note, which was updated in 2024, is intended as a dynamic tool to promote mutual learning opportunities and a better understanding of the principles.

Humanitarian action often takes place in areas affected by armed conflict. In many crisis situations, military presence can ensure the safety of the civilian population. Peacekeeping forces mandated to protect civilians can play an important role in this regard. Good dialogue between armed forces and humanitarian actors is crucial to promote and avoid unintended military attacks. Furthermore, there is a need for effective information sharing on humanitarian activities, civilians, and civilian infrastructure (known as deconfliction). The interplay between humanitarian actors, other civilian institutions and military actors can at times render principled humanitarian efforts difficult, if it creates uncertainty regarding roles, responsibilities, and objectives. This is especially the case where military forces/uniformed peacekeeping personnel participate in humanitarian tasks. Role confusion in relation to humanitarian, political and military actors can weaken the population’s trust in humanitarian organisations. This can also increase the risk of attacks on humanitarian aid workers. Some states also use emergency aid as part of a political or military strategy.

Nevertheless, to save lives, it is sometimes necessary for humanitarian operations to receive military support for logistical purposes or to gain safe access to those in need. The use of military assets in conflict situations presents dilemmas. Norway has supported the development of international guidelines19 with a view to ensuring that both international military support and support from individual countries in humanitarian crises is based on a clear division of roles. Although military contributions can fill humanitarian gaps, such engagement must be limited to exceptional situations and must be closely coordinated with humanitarian actors and the host country.

Norway’s policies on sanctions remain unchanged. Norway’s view is that multilateral and legally binding sanctions adopted by the UN Security Council, or other measures with broad international support, have the greatest legitimacy and coercive power to influence a state or other actors that threaten international peace and security. Norway has supported the EU’s restrictive measures with a few exceptions. It is important that sanctions regimes do not have unintended adverse consequences and hinder the work of humanitarian actors. Norway supports the inclusion of humanitarian exceptions in all sanctions regimes where this is relevant. A prerequisite for this is good dialogue with, and accountability on the part of, humanitarian partners to reduce the risk of misuse and diversion of funds. Norway will also seek to ensure that all international action against terrorism complies with international humanitarian law, the principles of the rule of law and international human rights law.

Box 3.4 Sanctions and humanitarian exceptions

The sanctions regimes currently implemented in Norwegian legislation are based on sanctions adopted by the UN Security Council and restrictive measures taken by the EU. The UN Security Council may impose sanctions to maintain or restore international peace and security in accordance with Article 41 of Chapter VII of the UN Charter. Sanctions adopted by the UN are legally binding for all UN Member States.

The EU adopts restrictive measures as part of its Common Foreign and Security Policy. The EU currently has over 40 different sanctions regimes in place targeting, for instance, conflict situations, regimes, and individual actors. Norway has supported the EU’s restrictive measures with a few exceptions.

Under international humanitarian law, all states are obliged to facilitate humanitarian access. The Norwegian Government places considerable emphasis on providing guidance to Norwegian actors to minimise the unintended adverse consequences of sanctions for humanitarian actors. This applies particularly to humanitarian actors whose mandate is to operate in areas affected by armed conflict, political instability, and humanitarian crises. Most Norwegian sanctions regulations will contain explicit exceptions for humanitarian actors from asset freezing provisions.

All Norwegian humanitarian organisations are expected to have good sanctions risk management procedures in place. Humanitarian actors should, to the extent possible, structure their operations in a way that reduces the risk of funds and assets becoming available to listed individuals and entities.

Chapter 4 A comprehensive approach

Humanitarian crises and armed conflicts have complex causes. We cannot prevent, remedy, or solve them by humanitarian means alone. In many societies, conflict resolution, development, disaster risk reduction, humanitarian response and recovery are needed simultaneously.

A comprehensive approach is required to address such multifaceted needs. Norway and most of our partners adhere to the OECD/DAC recommendation to prioritise prevention, mediation, and peacebuilding, invest in development where possible, while ensuring that immediate humanitarian needs are met – often referred to as triple nexus or a comprehensive approach.20 The purpose is to contribute to reducing vulnerability and humanitarian needs over time, enable crisis-affected populations to become more self-reliant, limit the humanitarian consequences of armed conflict and lay the foundation for prevention and resolution of conflicts through political processes.

New crises impact most severely already vulnerable societies characterised by poverty, weak institutions, climate change, deteriorating ecosystems and/or armed conflict. To contribute to resilient and stable societies and respond to humanitarian needs, we must make use of all of our policy instruments and consider them part of a coherent whole.

Humanitarian actors are increasingly operating with longer-term perspective as crises are becoming more protracted. They provide emergency response and seek more sustainable solutions to ensure services and protection. In addition to humanitarian action, there is a need to invest in preventive measures and work to address the underlying causes of crises and armed conflicts. The same applies to vulnerability to natural disasters. Instruments within development, conflict resolution and peacebuilding, as well as other relevant policy measures, must also be utilised in crisis-affected societies. A comprehensive approach is crucial to address issues such as food security, education and health. It is also essential in the efforts to support people affected by climate change and degraded ecosystems, as well as to find durable solutions for displaced people and to support their host communities.

Norway endeavours to ensure more coordinated policies between humanitarian assistance, development cooperation and peacebuilding to prevent and reduce the risk of protracted humanitarian crises.

The intentions of a comprehensive approach must be translated into practical policies. Each chapter in Part III of the Strategy identifies specific follow-up measures for humanitarian action and humanitarian policy that will contribute to a more comprehensive approach. This must be considered in conjunction with other relevant strategies, particularly regarding climate adaptation, food security and sustainable use and conservation of nature.

4.1 Coordination of humanitarian efforts, peacebuilding and long-term development assistance

We must emphasise the interaction between humanitarian action, conflict resolution and peace efforts. Humanitarian crises largely occur in states and communities affected by armed conflicts. This underscores the need for political solutions and conflict resolution at the national and local levels. Failure to protect civilians subjects the population to suffering and abuse which may undermine trust and the foundation for durable and peaceful solutions.

Norway invests considerable resources in conflict resolution, peace and reconciliation processes. These efforts are important to reduce humanitarian needs. We must also recognise and fund local actors engaging in conflict prevention and resolution through dialogue and mediation. Many of these actors implement measures which reduce conflict, facilitate integration of internally displaced people and reintegration of refugees, and enhance the resilience of local communities. Conflict reduction is an important prerequisite for development.

In contrast to humanitarian efforts, long-term development cooperation and stabilisationefforts can address the underlying causes of conflict and vulnerability. To this end, poverty eradication, institution building, good governance, human rights and gender equality are key. Development and stabilisation actors can bolster the capacity of governments and local communities to manage and prevent crises, develop early warning and preparedness systems, and ensure the provision of basic services for the population.

Development actors should engage at an early stage in humanitarian crises, as they bring both long-term development expertise and more sustainable financing. This also applies to support for displaced people and their host communities. The UN and the multilateral development banks play an important role in this respect. There is a need for greater flexibility and tolerance of not achieving planned results in long-term development efforts in fragile states and regions. Prevention and reduction of the scale of humanitarian crises should therefore be an explicit goal of development cooperation, alongside development goals such as poverty eradication.

Many of the organisations Norway supports have broad mandates covering humanitarian, long-term development cooperation and peace efforts.

A well-functioning UN and cooperation with non-governmental organisations and national and local authorities where possible, are important to ensuring efficient and comprehensive efforts. In this context, the UN Resident Coordinator, who also serves as Humanitarian Coordinator in countries affected by humanitarian crises, plays a key role.

The World Bank and the regional development banks particularly stress the importance of partnerships with the UN, the private sector and civil society in fragile and conflict-affected situations. In recent years, the World Bank has increased its presence and strengthened measures in crisis-affected countries and adopted new tools for crisis preparedness and response. Norway is also a driving force behind the increasingly closer collaboration between the UN and the World Bank on conflict prevention and peacebuilding.

Box 4.1 Cash-based assistance programme for comprehensive action in Somalia

Somalia has experienced protracted crises since the collapse of the Somali state during the civil war in the 1990s. Armed conflict, the struggle for scarce natural resources and climate change render Somalia increasingly vulnerable to new humanitarian crises. Norway has supported the reconstruction of Somali institutions and economic reforms in tandem with humanitarian assistance. Through the World Bank, Norway has supported the Shock Responsive Safety Net for Human Capital Project (BAXNAANO). The programme is implemented by the Somali Ministry of Labour and Social Affairs with support from UN agencies including the WFP and UNICEF. Since 2019, BAXNAANO has provided cash assistance to 220,000 low-income households. Through a dedicated crisis response window, cash assistance has been provided to an additional 615,000 households, thereby strengthening their resilience to humanitarian crises caused by locust infestations and drought.

4.2 Comprehensive efforts against hunger

Photo: © WFP/Gabriela Vivacqua

Disaster prevention is crucial to addressing the global hunger crisis. In principle, this should be a component of long-term assistance. However, it often requires a comprehensive approach whereby long-term development, humanitarian and peacebuilding actors must cooperate with local authorities and the international community. Preventing violent conflict and contributing to peacebuilding in areas affected by war and instability will reduce the risk of hunger crises. The most vulnerable populations must be far better protected against food crises, and the use of starvation as a method of warfare must end.21 Improved food security can prevent humanitarian disasters and reduce humanitarian needs.22 Climate adaptation measures must be prioritised. Our aid will contribute to building resilient local communities that are able to avoid food shortages and hunger catastrophes. This necessitates increased emergency preparedness capacity, the strengthening of social safety nets and insurance mechanisms against extreme weather events.

4.3 Preparedness and disaster risk reduction for natural disasters

Photo: © UNHCR/Andrew McConnell

Disaster prevention, preparedness and recovery following natural disasters, including climate-related events, are key to Norway’s development policy. The humanitarian crisis response must be intricately linked to all phases of such efforts, with the aim of reducing the humanitarian consequences.

The Sendai Framework contains a set of agreed global targets and indicators for disaster risk reduction and has also elevated disaster risk reduction and preparedness on the international agenda. The UN Office for Disaster Risk Reduction (UNDRR) coordinates disaster risk reduction efforts in the UN system and is responsible for implementing the Sendai Framework.

There is a clear correlation between climate adaptation, preservation of nature, prevention of climate and natural disaster, and the need for humanitarian efforts. Prevention of and preparedness for extreme weather events, earthquakes and other natural phenomena are costly, however, disaster response and recovery have a much higher cost. Low-income countries and vulnerable groups are disproportionately affected.

Norway supports the financing of climate-resilient recovery and reconstruction through multiple channels. Recovery and reconstruction are components of the work on loss and damage associated with the adverse effects of climate change, and form part of the funding arrangements implemented following COP28, including the newly established Fund for responding to Loss and Damage.

Humanitarian actors can play a role in disaster prevention, preparedness, and recovery efforts. However, it is primarily the development actors that must further these efforts, in cooperation with local authorities.

During the strategy period, we will support preparedness, risk reduction, nature conservation and climate adaptation efforts as part of a comprehensive approach to reduce vulnerability and humanitarian needs.

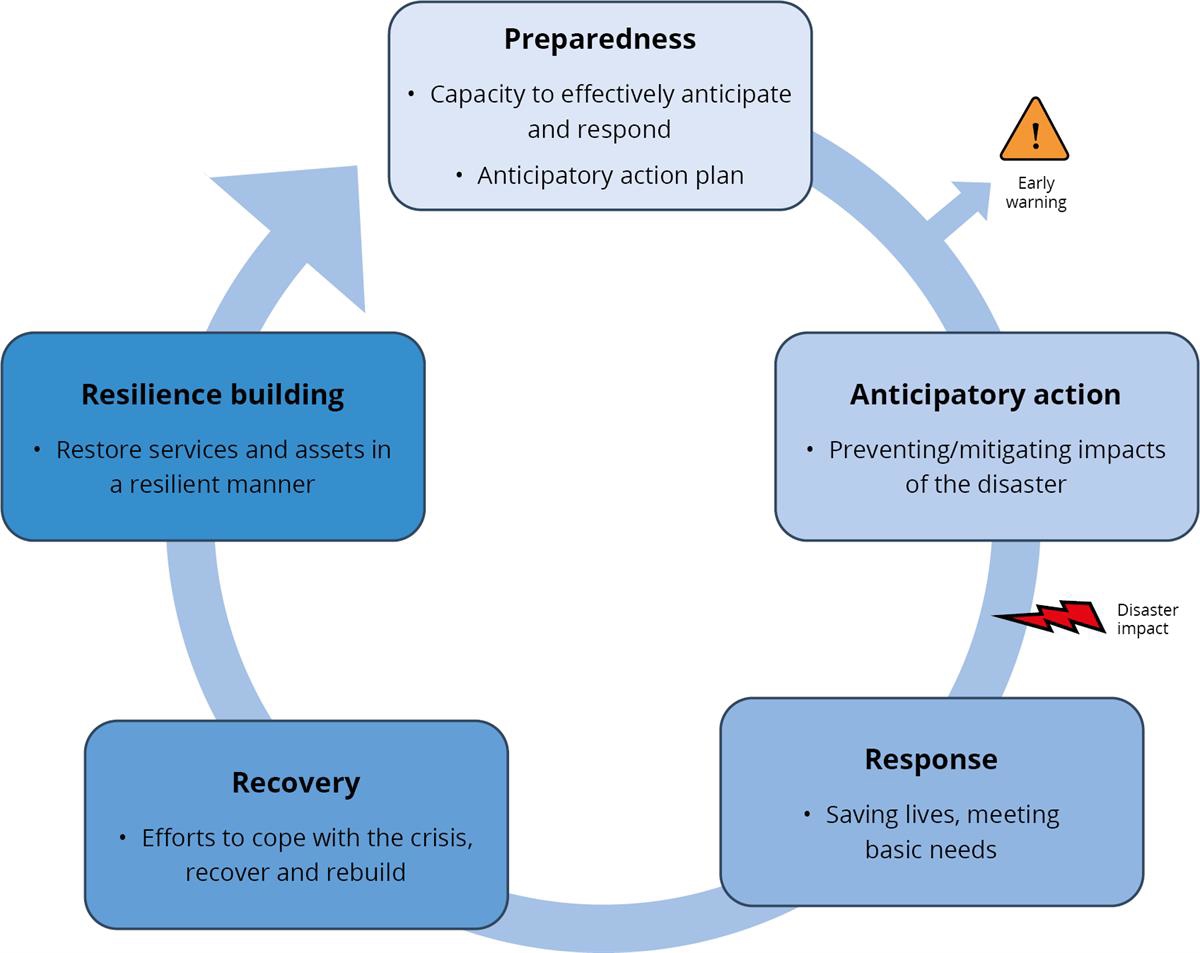

Box 4.2 Anticipatory action – a forecast-based approach

The purpose of anticipatory action is to reduce the humanitarian consequences of extreme weather events by acting before the event occurs. About half of all disasters can be predicted, and about a quarter can be predicted with a high degree of certainty.23 In order to act ahead of a crisis, there is a need for high-quality analyses of weather and climate data and of how droughts and floods have previously impacted food production and food security for various segments of the population. Therefore, it is important to strengthen local and national weather and climate forecasting capacity.

Norway supports anticipatory action across the climate, development, and humanitarian sectors, including through the World Food Programme (WFP) and the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). Anticipatory action is now an integral part of the UN Central Emergency Response Fund (CERF) and the Disaster Response Emergency Fund (DREF) of the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC).

Figure 4.1 The figure is a schematic representation of the different stages of anticipatory action.

4.4 Dilemmas arising in interaction

To ensure that crisis-affected populations have access to basic services, humanitarian organisations may assume responsibility for maintaining infrastructure and services that are normally within the purview of the government. There are often good reasons for humanitarian organisations to assume responsibility for such tasks, including early recovery. This is especially the case where the political situation precludes cooperation with the authorities and development actors are not present. The efforts of humanitarian actors can contribute to preventing system collapse and are necessary to save lives and alleviate suffering, contributing to more efficient use of resources. Preventing system collapse helps avoid the need for more costly mitigating measures to meet the basic needs of the population.

However, this should not be a long-term responsibility of humanitarian actors. It risks diverting capacity from other, more acute, crises, and humanitarian actors also risk being perceived as biased due to close ties to the authorities. In protracted conflict situations, humanitarian actors face difficult dilemmas if their operations are perceived as contributing to the continuation of conflict and maintaining of authoritarian regimes. This may occur if parties to a conflict or authorities use resources on warfare or oppression, leaving the responsibility for basic services to humanitarian organisations. It must always be a prerequisite that humanitarian action is carried out in accordance with the humanitarian principles. There must be a clear division of roles and responsibilities among the different actors.

It is important that humanitarian organisations, where possible and expedient, interact with, and subsequently transfer tasks to, authorities or actors with competence and resources to carry out long-term development work. This is necessary for the humanitarian response to be phased out.

More effective and coordinated efforts at the intersection of humanitarian action, development and peacebuilding also require changes on the part of donors, including Norway. For instance, this may involve a greater degree of coordination of and cooperation on the management of funds for these efforts, particularly at the country level. Norwegian embassies play a key role by providing comprehensive assessments and analyses.