4 Status of marine conservation in Norway and future developments

Norway has jurisdiction over ocean areas that support important species and habitat types, and where ocean-based activity is increasing and there are emerging ocean industries. Clean and healthy oceans are an essential basis for a sustainable ocean economy. Biodiversity underpins ecological productivity, providing a basis for harvesting; it also makes ecosystems adaptable and is the basis for food production from the oceans. Value creation in the future will depend on maintaining good environmental status and high biodiversity in seas and oceans.

Over the years, a great deal of work has been put into developing an integrated, sustainable management regime for all Norway’s marine areas. The Norwegian ocean management plans have provided a model for the work of the Ocean Panel. Marine protection and other effective area-based conservation measures, together with policy instruments for sustainable use, are key elements of integrated, sustainable ocean management. By focusing more on conservation measures, Norway can strengthen its integrated ocean management regime and follow up the Ocean Panel’s conclusions.

There is growing activity in emerging ocean industries such as offshore wind, offshore aquaculture and marine bioprospecting. Carbon storage below the seabed, hydrogen production and mineral extraction from the seabed also have potential as future ocean industries.

Valuable biodiversity is identified through sustained knowledge building. Knowledge about the marine environment has been developing rapidly in recent years. Instruments for the conservation of valuable biodiversity and marine ecosystem services will be developed on the basis of new knowledge acquired through mapping, monitoring and research.

Norway’s position is that decisions to establish marine protected areas (MPAs) must have a sound scientific basis. The purpose of protection must be clearly defined. Conservation measures must be effective and targeted, and also appropriate for ensuring long-term protection of the natural environment and ecosystems. It is not a requirement under the Nature Diversity Act that an area must be under pressure to be designated as an MPA.

In international forums, Norway has emphasised that it is not sufficient to set ambitious percentage targets for marine protection and other conservation measures. It is also necessary to define requirements for the substance of protection measures, including their scientific basis and their governance and management. Norway’s ocean management regime is still being developed and has many important features that can be included in reporting to international forums. This applies both to conservation measures and to instruments to ensure sustainable use.

4.1 Status report on the 2004 marine protection plan

Norway has been working on area-based conservation of the marine environment for many years. The 1954 Nature Conservation Act applied explicitly to areas of both land and water. In this connection, the legislative history of the Act pointed out that it might be appropriate to introduce protection of coral reefs, and that fishing and kelp trawling could be prohibited. The 1970 Nature Conservation Act did not specify how it applied to marine areas, and therefore applied to Norwegian territory out to the territorial limit.

The 1999 white paper on conservation and use in coastal waters and the relationships between conservation interests and the fisheries industry set out guiding principles for further work on marine protection. The white paper concluded that in the context of conservation, the coastal zone was more poorly represented than inland areas. At the same time, it was decided to appoint an advisory committee to develop a marine protection plan. The committee included representatives from the public administration and relevant interest organisations.

In 2001, the committee was appointed by the Ministry of the Environment, in consultation with the Ministry of Fisheries. On the basis of an analysis of the distribution of benthic marine species and other information, the coast was divided into three biogeographical regions. Possible protected areas were divided into six categories. The committee sought to select areas from all six categories in each of the three biogeographical regions. It was also considered important to find distinctive and representative areas for each region and stretch of coastline, and that the areas selected were relatively undisturbed and could serve as reference areas for research and monitoring.

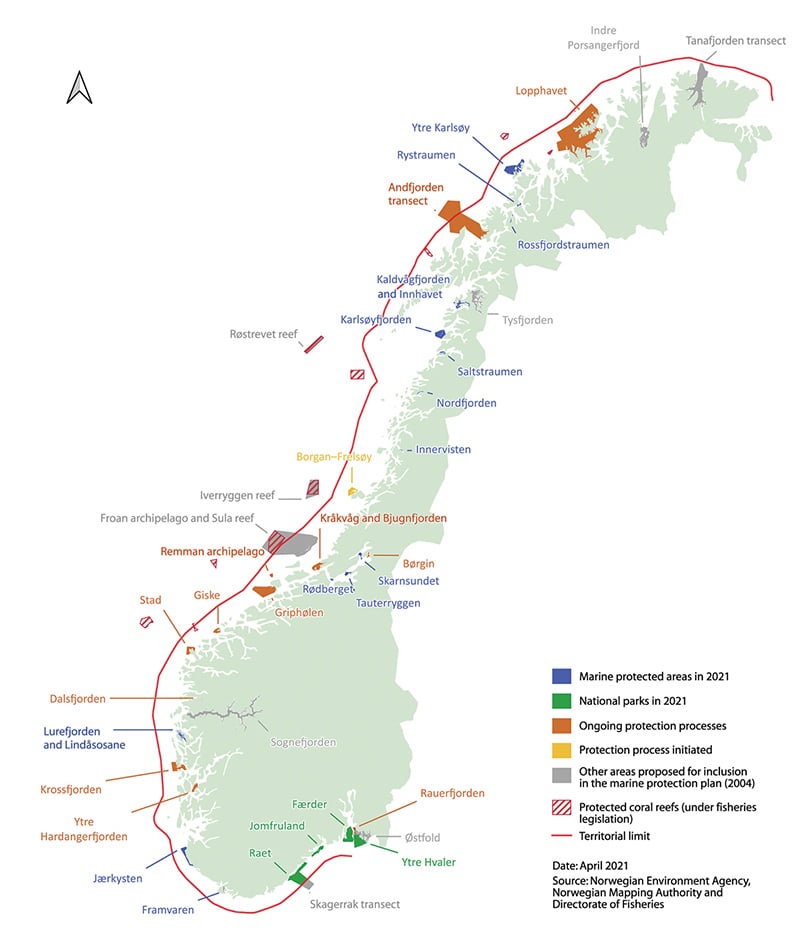

In its final recommendations in 2004, the committee identified 36 areas which together provided a good, representative selection of marine nature along the mainland coast, including islands and skerries. Fifteen of these have since been established as marine protected areas under the Nature Diversity Act. Additionally, one area has been protected as part of Raet National Park. For a further three areas, which are partly or entirely outside the territorial limit, marine protected areas under the Marine Resources Act have been implemented. Protection processes under the Nature Diversity Act have been announced for several other areas.

In its recommendations, the advisory committee focused on coastal waters, including islands and skerries. At the same time, the committee called attention to the need to expand the scope of this work to areas further from the coast during phase 2 of the development of the marine protection plan. Implementation of the 2004 plan and preparation of phase 2, to include areas further from the coast, will be important in the time ahead.

Figure 4.1 Dalsfjorden.

Source Vestland County Governor’s Office/Maria Knagenhjelm

Table 4.1 Status of areas recommended for inclusion in the marine protection plan in 2004.

County | Area | Status |

|---|---|---|

North Sea–Skagerrak | ||

Viken | Rauerfjorden (Østfold) | Ongoing protection process (coral reef already protected under fisheries legislation) |

Agder | Skagerrak transect | Protected in 2016 as part of Raet National Park |

Agder | Framvaren | Protected in 2013 |

Rogaland | Jærkysten | Protected in 2016 |

Vestland | Ytre Hardangerfjorden | Ongoing protection process |

Lurefjorden and Lindåsosane | Protected in 2020 | |

Krossfjorden | Ongoing protection process | |

Vestland | Sognefjorden | Not started |

Dalsfjorden | Ongoing protection process | |

Norwegian Sea | ||

Stad | Ongoing protection process | |

Møre og Romsdal | Giske | Ongoing protection process |

Griphølen | Ongoing protection process | |

Remman archipelago | Ongoing protection process, part designated as a nature reserve | |

Trøndelag | Gaulosen | Protected in 2016 |

Rødberget | Protected in 2016 | |

Froan archipelago and Sula reef | Not started, Sula reef protected under fisheries legislation | |

Kråkvåg and Bjugnfjorden | Ongoing protection process | |

Trøndelag | Tauterryggen | Protected in 2013 |

Børgin | Ongoing protection process | |

Skarnsundet | Protected in 2020 | |

Borgan–Frelsøy | Protection process initiated | |

Nordland | Saltstraumen | Protected in 2013 |

Innervisten | Protected in 2020 | |

Nordfjorden (Rødøy municipality) | Protected in 2020 | |

Karlsøyvær | Protected in 2020 | |

Kaldvågfjorden and Innhavet | Protected in 2020 | |

Tysfjorden | Not started | |

Barents Sea–Lofoten area | ||

Nordland/Troms og Finnmark | Andfjorden transect | Ongoing protection process |

Troms og Finnmark | Rossfjordstraumen | Protected in 2020 |

Rystraumen | Protected in 2020 | |

Ytre Karlsøy | Protected in 2020 | |

Troms og Finnmark | Lopphavet | Ongoing protection process |

Indre Porsangerfjord | Not started | |

Tanafjorden transect | Not started | |

Outside territorial waters | Iverryggen reef Røstrevet reef | Protected under fisheries legislation Protected under fisheries legislation |

Source Norwegian Environment Agency/Ministry of Climate and Environment

Figure 4.2 Map of existing and planned marine protected areas.

Source Norwegian Environment Agency, Norwegian Mapping Authority and Directorate of Fisheries

Progress in implementing marine protection in Norway

As mentioned before, 15 MPAs have so far been established under the Nature Diversity Act. These are situated along much of the mainland coast of Norway, with three MPAs in Troms og Finnmark county, four in Nordland, four in Trøndelag, one in Vestland, one in Rogaland and one in Agder. However, more MPAs are needed to supplement the list and provide a representative selection of habitat types in coastal waters. In addition, the current MPAs provide little coverage of areas further from the coast.

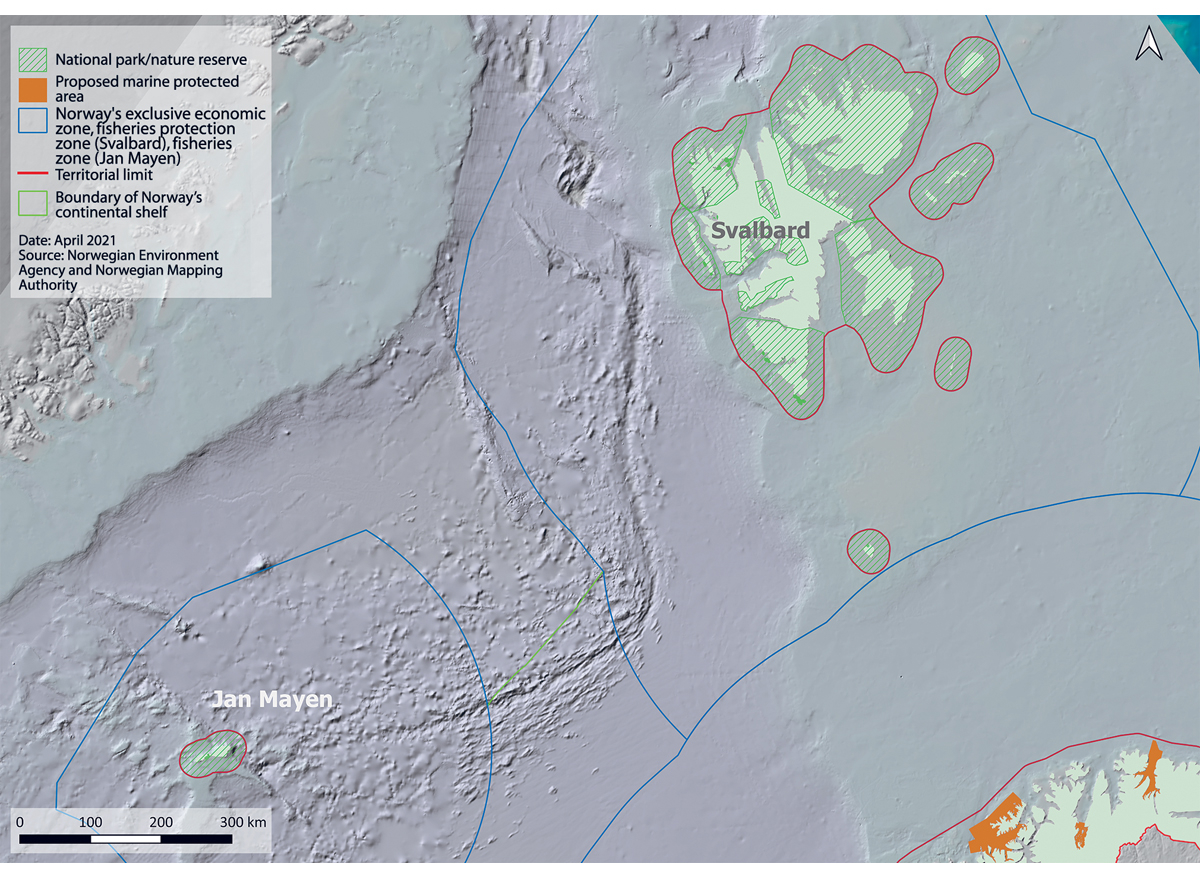

Figure 4.3 Protected areas in and around Svalbard and Jan Mayen.

Source Norwegian Environment Agency

Several national parks also include marine areas, including Ytre Hvaler national park in Viken county, Færder national park in Vestfold og Telemark, and Raet national park in Agder. Protection of the marine environment is an important part of the purpose of protecting these areas. In all, areas protected under the Nature Diversity Act cover about 3.6 % of the territorial waters around mainland Norway.

About 87 % of the territorial waters surrounding Svalbard are included in areas that are protected under the Svalbard Environmental Protection Act. The Jan Mayen nature reserve includes the territorial waters around the island. The territorial waters around Bouvet Island are protected under the Act relating to the Norwegian dependencies.

In total, areas protected under environmental legislation cover about 4.2 % of Norwegian waters.

4.2 Future conservation efforts, particularly for areas beyond the 12 nautical mile limit

There is growing recognition that there are areas of importance for marine biodiversity in all parts of the oceans. As explained in Chapter 1, the conservation of areas of importance for marine biodiversity is an integral part of a sustainable ocean economy.

4.2.1 Knowledge about and identification of important areas

There is a generally sound knowledge base for assessing species and habitats and areas of particular conservation value in Norway’s coastal waters, as discussed for example in Chapter 2. This knowledge base was used to identify the coastal areas proposed as MPAs in the 2004 marine protection plan. It has also been important for the establishment of other area-based conservation measures within the territorial limit, for example no-take zones for lobster and reference areas for kelp forest. In addition, when more candidate MPAs are proposed for coastal areas in the future, this knowledge will be a sound basis for adopting clearly targeted, effective conservation measures.

For areas further from the coast, the level of knowledge on areas that are particularly important for biodiversity and ecosystem services is more variable and there is often less detailed information. Assessments of knowledge and information that can be used to identify areas of importance for marine biodiversity are generally carried out in connection with Norway’s ocean management plans. This applies especially to the identification of particularly valuable and vulnerable areas, which involves a thorough scientific process involving all relevant research institutes and government agencies. The existing system of particularly valuable and vulnerable areas covers 42 % of Norwegian waters.

As explained in the ocean management plans, the designation of areas as particularly valuable and vulnerable does not have any direct effect in the form of restrictions on commercial activities, but indicates how important it is to show special caution in these areas, and to ensure that activities are carried out in a way that does not threaten their ecological functioning or biodiversity. To protect valuable species and habitats, it is for example possible to use current legislation to introduce special requirements for activities in such areas. Such requirements may apply to the whole of a particularly valuable and vulnerable area or part of it, and must be considered on a case-by-case basis.

The current set of particularly valuable and vulnerable areas is being reviewed and updated on the basis of new knowledge. The review is to be completed early in 2022 and will be used in the preparation of the next white paper on the ocean management plans, to be published in 2024. The review of the particularly valuable and vulnerable areas will also provide a good basis for developing a more systematic approach to assessing how various measures contribute to the effective conservation of areas of importance for biodiversity in Norwegian waters. There are also large ocean areas that are afforded effective protection through measures under sectoral legislation, based on knowledge of biodiversity built up through long-term, extensive marine scientific research.

4.2.2 Marine protection

The Nature Diversity Act generally applies out to the territorial limit, except for certain provisions, including those on general principles, which also apply to Norway’s 200 nautical mile economic zone and on the continental shelf to the extent they are appropriate. This means that the authorities must for example base their decisions on scientific knowledge and the cumulative environmental effects on ecosystems. The precautionary principle also applies to waters beyond the 12 nautical mile limit. The provisions of the Nature Diversity Act on marine protected areas do not apply beyond 12 nautical miles. On the other hand, sectoral legislation such as the Marine Resources Act provides the authority for various types of area-based conservation measures, which make an important contribution to the conservation and sustainable use of ocean areas. The same applies to conditions set for oil and gas activities under the petroleum legislation.

In areas inside the territorial limit where there are distinctive and rare species and habitats, it has been decided that it is necessary to be able to provide protection across sectors, so that the activities that can be permitted in an area are determined by its conservation value. If an area is used for several different types of activities, it is useful to introduce measures that take into account the cumulative effects of all the activities on the marine environment. The establishment of protected areas is based on their conservation value, not a specific activity, in order to maintain species and habitats in the long term, and regardless of whether or not an area is currently under pressure.

Norway’s system of ocean management plans provides an overview of environmental pressures and impacts and of regulatory measures. In the white paper Norway’s integrated ocean management plans for the Barents Sea–Lofoten area; the Norwegian Sea; and the North Sea and Skagerrak (Meld. St. 20 (2019–2020)), the Government called attention to the need to consider marine protection and other area-based conservation measures for distinctive and rare species and habitats in deep-sea areas.

The Institute of Marine Research has recently published an expert evaluation of work on marine protection in Norway. This identified a need to protect coral reef areas against other activities in addition to fisheries. In the report, the Institute also mentions the importance of protecting transects stretching from the coast to deep-water areas. Raet national park is an example of a protected area that is delimited by the territorial limit, even though important species and habitats and the need for protection extend further out from the coast. The 2004 marine protection plan includes the Froan archipelago/Sula reef area and the Andfjorden transect, which are other examples of where of conservation value that extend further out to sea than the 12 nautical mile limit.

According to the legislative history of the Nature Diversity Act (Proposition No. 52 (2008–2009) to the Storting), an assessment of the relationship of certain provisions of the Act to international law revealed that amendments and adjustments would be needed if they were to be made applicable beyond 12 nautical miles from the baselines. It would also be necessary to make a thorough evaluation of the relationship of these provisions to sectoral legislation and of the social and environmental consequences of making them applicable to Norway’s continental shelf and areas of jurisdiction established outside the territorial limit. The Government stated that it would therefore make a thorough assessment of whether and how other provisions of the Nature Diversity Act should be made applicable beyond the 12-nautical-mile limit. This assessment has not yet been carried out.

Figure 4.4 Protection of coral reefs against damage from fisheries activities.

Source Norwegian Environment Agency, Norwegian Mapping Authority and Directorate of Fisheries

4.2.3 Other effective area-based conservation measures

Other effective area-based conservation measures (OECMs) are measures under sectoral legislation that make an important contribution to the conservation of areas of importance for marine biodiversity. OECMs must be managed to deliver sustained positive outcomes for the conservation of biodiversity in an area. OECMs may be established both within and beyond the 12 nautical mile limit.

In the white paper on Norway’s national biodiversity action plan (Meld. St. 14 (2014–2015)), the Government stated that not only protected areas under the Nature Diversity Act, but also conservation measures under other legislation, may be identified as ‘other effective area-based conservation measures’ as mentioned in Aichi target 11. To be designated as OECMs, measures must provide a sustained and effective contribution to the conservation of geographically delineated areas that support valuable biodiversity. In 2018, the parties to the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) adopted voluntary guidance on OECMs, including criteria for the types of area-based regulatory measures that can be identified as OECMs. The criteria are divided into the following categories:

A. The areas is not currently recognised or reported as a marine protected area (MPA).

B. The area is governed and managed by the competent authorities and its boundaries are geographically delineated.

C. Regulation achieves sustained and effective contribution to in situ conservation of biodiversity in the area.

D. Associated ecosystem functions and services and cultural, spiritual, socio-economic and other locally relevant values are supported and upheld.

As mentioned in Chapter 3, the parties must take action to achieve Aichi target 11, especially for ‘areas of particular importance for biodiversity and ecosystem services’. In other words, the use of OECMs should focus particularly on areas of the marine environment that are considered to be most important. These include communities including rare or threatened species, representative natural ecosystems, species with a limited distribution, key biodiversity areas, areas that support critical ecosystem functions and services, and areas of importance for ecological coherence. It is also important to consider areas where the environment is undisturbed, particularly on the seabed, even though we often lack detailed knowledge about such areas.

Norway has not yet developed a systematic approach to identifying measures in the fisheries sector and other sectors, such as the petroleum sector, that can be defined as OECMs. A systematic approach will be needed to assess the overall effect of conservation measures on areas of importance for biodiversity in Norwegian waters. This will become increasingly important with the anticipated expansion of activities in Norway’s ocean areas, for example the development of offshore wind power and mineral extraction from the seabed in deep-water areas on the Norwegian continental shelf.

Figure 4.5 Part of a coral reef. Norwegian coral reefs are largely formed by the cold-water coral Lophelia pertusa. Coral reefs are biodiversity hotspots that provide a habitat for many other species, and play an important role in the carbon cycle on the seabed.

Source Erling Svensen/Institute of Marine Research

Protection of coral reefs under fisheries legislation

Eighteen cold-water coral reef areas along the coast have been designated as marine protected areas under the Marine Resources Act. This makes an important contribution to the conservation of the marine environment. The 18 areas are shown on the map in Figure 1.4:

Korallen

Fugløyrevene

Sotbakken

Hola

Røstrevet

Trænarevet

Iverryggen

Sularevet

Breisunddjupet

Storneset

Aktivneset

Straumsneset

Nakken

Midtsundrevet

Tisler (in Ytre Hvaler nastional park)

Fjellknausane

Rauerfjorden

Søndre Søster

The Froan archipelago/Sula reef area and the Iverryggen reef

When it considered the white paper Update of the integrated management plan for the Norwegian Sea (Meld. St. 35 (2016–2017)), the Storting (Norwegian parliament) asked the Government not to initiate new petroleum activities, including exploration and seismic surveys, in the Froan archipelago/Sula reef area and the Iverryggen reef area until an overall marine protection plan for all Norwegian sea areas was presented to the Storting. This decision was retained as part of the framework for petroleum activities in the Barents Sea–Lofoten area in the white paper Norway’s integrated ocean management plans for the Barents Sea–Lofoten area; the Norwegian Sea; and the North Sea and Skagerrak (Meld. St. 20 (2019–2020)).

There is no new knowledge to indicate that this decision should be reassessed in connection with the present white paper. As mentioned earlier, all the particularly valuable and vulnerable areas are being reviewed as part of the work on Norway’s ocean management plans. The Government will therefore retain the decision not to initiate new petroleum activities in the Froan archipelago/Sula reef area and the Iverryggen reef area until the next white paper on the ocean management plans, which is scheduled for 2024.

Other measures in the fisheries sector

In addition to measures to protect coral reefs, other conservation measures under fisheries legislation may be recognised as effective area-based conservation measures. Regulatory measures that prohibit or limit the use of fisheries gear may make an important contribution to the conservation of biodiversity, particularly on the seabed. Prohibiting trawling in areas that are important for marine biodiversity can for example have a positive effect by reducing disturbance to benthic habitats.

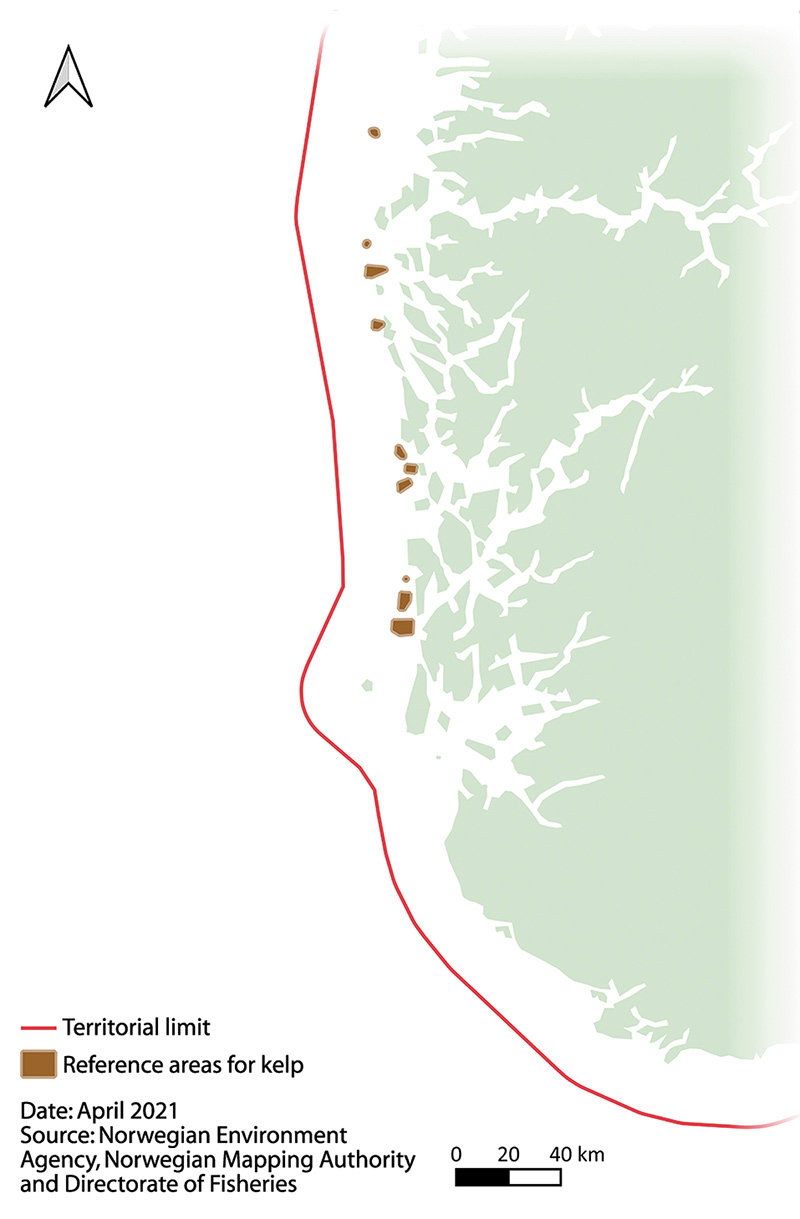

Figure 4.6 No-take zones for lobster along the Skagerrak coast.

Source Norwegian Environment Agency, Norwegian Mapping Authority and Directorate of Fisheries

During the preparation of this white paper, the Norwegian Environment Agency and the Directorate of Fisheries, with support from the Institute of Marine Research, have made an initial evaluation of the extent to which other relevant measures under fisheries legislation can be recognised as OECMs. In addition to measures to protect coral reefs, these include no-take zones for lobster, regulatory measures for kelp trawling and the closure of areas around Svalbard to fisheries.

No-take zones for lobster. The establishment of no-take zones is a suitable approach for a relatively stationary species like the lobster, and has been shown to boost lobster numbers locally. A number of no-take zones have been established along the Skagerrak coast, and lobster numbers have risen both within these zones and in surrounding waters. No-take zones have had positive effects for cod and wrasses as well as lobsters. A number of the no-take zones have now been made permanent.

Reference areas for kelp. Regulations on kelp harvesting specify a five-year rotation system for harvesting areas, which are divided into strips with a breadth of one nautical mile. Within the harvesting areas, there are reference areas where harvesting is prohibited and kelp forests remain undisturbed.

Figure 4.7 Reference areas for kelp.

Source Norwegian Environment Agency, Norwegian Mapping Authority and Directorate of Fisheries

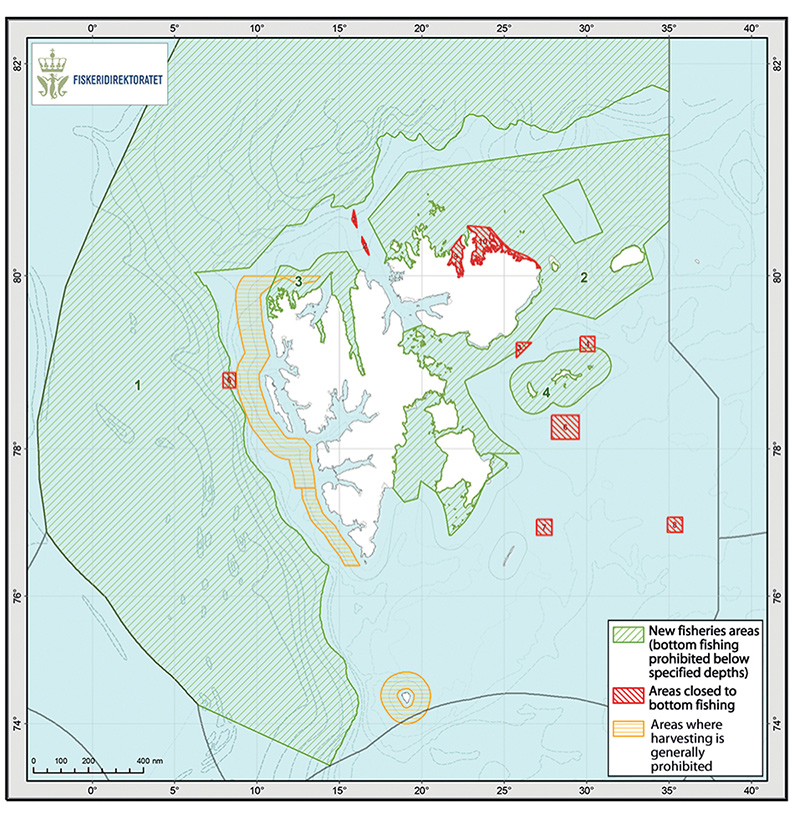

Areas around Svalbard that are closed to bottom fisheries. Section 5 of the Regulations relating to regulatory measures for fishing to protect vulnerable marine ecosystems prohibits fishing with bottom gear in ten selected areas. The basis for these closures is that the information available indicates that there are vulnerable species and habitats in the areas in question. In addition, they have not previously been fished, or only to a limited extent. The areas closed under section 5 of the regulations are a parallel to the restrictions on fishing activities in coral reef areas described above.

Figure 4.8 Map showing different categories of areas around Svalbard where fishing is restricted or prohibited.

Source Directorate of Fisheries

Areas where fishing using bottom gear is prohibited below certain depths in order to protect vulnerable marine ecosystems. South of Bjørnøya, fishing is prohibited at depths of more than 1000 metres. North of Bjørnøya, the limit is 800 metres, with one important exception, a large shallow area known as the Yermak Plateau north of the island of Spitsbergen, where the limit is only 300 metres. These areas are generally closed to fisheries, but it is possible to apply for permits for exploratory fishing, which will only be granted subject to strict conditions. In their evaluation of fisheries measures, the Norwegian Environment Agency and the Directorate of Fisheries concluded that this measure in itself makes an effective contribution to the conservation of marine biodiversity. In its evaluation of work on marine protection in Norway, the Institute of Marine Research concluded that area-based measures that prohibit or restrict the use of trawling gear can make an important contribution to the conservation of biodiversity, and that areas where bottom trawling is prohibited could therefore generally be recognised as OECMs if there are no other significant threats from human activity. The Institute also pointed out that benthic communities play an important role in the entire ecosystem, but have in many areas been depleted, for instance by prolonged, frequent bottom trawling. Soft sediments that remain undisturbed also make an important contribution to carbon sequestration, which is important in the context of climate change.

Figure 4.9 Areas deeper than 1000 metres where fishing with bottom gear is prohibited (the limit is 800 metres from Bjørnøya and northwards).

Source Norwegian Environment Agency, Norwegian Mapping Authority and Directorate of Fisheries

Other measures that have been assessed for inclusion as OECMs are the prohibition on harvesting of European flat oysters in parts of Sørlandsleia (sheltered waters between the mainland and islands and skerries near Arendal), and the general prohibition on harvesting in specified areas in the fisheries protection zone around Svalbard.

The preliminary conclusion is that the measures discussed above meet several of the criteria for recognition as ‘other effective area-based conservation measures’. In all, these measures apply to 44 % of Norwegian waters. If all the area-based fisheries measures are recognised as OECMs, this would increase the proportion of Norway’s waters covered by marine protection or OECMs to about 49 %.

Measures in other sectors

A systematic approach to identifying measures that can be considered as OECMs must also include the conservation effect of measures in sectors other than the fisheries. One obvious example is the framework for petroleum activities in specific geographical areas set out in the ocean management plans, which includes areas where petroleum activities are restricted. For example, licences for petroleum activities will not be issued for areas where the management plans specify that there are to be no petroleum activities. Nor will petroleum activities be permitted at times of year when a decision has been taken not to permit exploration drilling. The framework for petroleum activities includes restrictions of these kinds covering about 11 % of the area covered by the management plan for the Barents Sea–Lofoten area, about 12 % of the Norwegian Sea management plan area, and about 2 % of the North Sea–Skagerrak management plan area.

Similarly, areas subject to measures included in the framework for other types of activities, such as offshore wind power, could be candidates for inclusion as OECMs in the future.

The need for further work

The initial evaluation of fisheries measures by the Directorate of Fisheries and the Norwegian Environment Agency is a good starting point for a more systematic approach to identifying the sectoral measures that can be recognised as OECMs. Relevant conservation measures need to be further assessed. This work should include assessments of the components of marine biodiversity for which areas are important and overall evaluations of pressures and impacts on biodiversity from different activities.

The Institute of Marine Research has pointed out that several types of activity that are now restricted to coastal waters may be expanded further offshore in the future. Further, regulating only one of several activities causing environmental pressures in an area will not necessarily be sufficient to satisfy the criteria for identifying the area as an OECM. According to the Institute, this means that in areas where there are also significant pressures from human activities (for example petroleum activities, aquaculture, defence activities, seabed mineral extraction or substantial pressure from other types of fisheries), area-based measures that only involve a prohibition on bottom trawling may not be sufficient to provide effective protection of biodiversity.

In order to determine which fisheries measures can be recognised as OECMs, overall assessments are needed that also include activities in other sectors and how they are regulated. Among other things, this is necessary to ensure that the effects of conservation measures in one sector are not cancelled out by activities in other sectors. In some cases, measures in different sectors may amplify each other’s effects.

4.3 Reporting on progress towards international conservation targets in the future

Now that Norway has given its support to the Ocean Panel’s global target of protecting 30 % of the oceans by 2030 through marine protected areas and other effective area-based conservation measures, and the same target has been proposed for the post-2020 global biodiversity framework under the CBD, it is natural to reassess Norwegian routines for reporting on progress towards targets. Norway has until now provided status reports in line with the guidelines set out in the white paper on Norway’s national biodiversity action plan (Meld. St. 14 (2015–2016)) and further guidelines adopted by the Storting during consideration of the white paper. The Standing Committee on Energy and the Environment concluded that only measures that make a sustained contribution to conservation, such as protection under the Nature Diversity Act and protection of marine areas under other legislation, together with protection under the Svalbard Environmental Protection Act, that can be included in reporting on progress towards Aichi target 11. Marine areas protected under the Nature Diversity Act, the Svalbard Environmental Protection Act and the Act relating to the Norwegian dependencies make up about 4.2 % of Norwegian waters around mainland Norway, Svalbard, Jan Mayen and Bouvet Island. If coral reef areas designated as marine protected areas under the Marine Resources Act are included, this rises to about 4.5 %.

Compared with other countries, Norway has so far taken a relatively restrictive approach to reporting on its contributions to achieving international conservation targets. It is particularly natural to adjust the current reporting routines by considering how more OECMs, for example in the fisheries sector, can be included in the figures when Norway reports to the CBD. At the same time, the fundamental standards for the substance and quality of conservation measures in the areas that are included in reports must be maintained. In adjusting the routines, there will be a special emphasis on areas of particular importance for biodiversity and ecosystem services and on whether conservation measures protect their value effectively.

Integrated, sustainable ocean management involves a combination of marine protection, OECMs and measures to ensure value creation through sustainable use. This was emphasised by the Ocean Panel, which based its commitment to sustainable management 100 % of the ocean area under national jurisdiction on the conclusion that both conservation and sustainable use are essential components of a sustainable ocean economy. To follow up the commitment by the Ocean Panel, it may be appropriate to develop a separate reporting system to show whether countries are meeting the 100 % target for sustainable ocean management.