The digital divide – technology and opportunity

2 Barriers – the digital divide

Figur 2.1

2.1 The global picture

For developing countries to make use of digital technology, and for the resulting benefits to be widely shared, the digital gap must be narrowed and barriers must be removed. This means developing the necessary infrastructure, instituting regulations, tailoring relevant digital solutions to local conditions and boosting local knowledge and expertise.

Norway will focus its efforts on four barriers in particular: access, regulation, digital competence and exclusion.

2.1.1 Access

Access to internet is covered by the Sustainable Development Goal 9, “Build resilient infrastructure, promote inclusive and sustainable industrialization and foster innovation”, with target 9c aiming to “significantly increase access to ICT and strive to provide universal and affordable access to internet in LDCs by 2020”. In addition, access to internet is considered as key to achieve a number of the other goals.

The internet is used by 4.4 billion people, or 57 per cent of the world’s population, and the number is rising quickly. Since January 2018 it has increased by a million users per day. Nevertheless, there are still 3.3 billion people who are not internet users. Most of them live in Southeast Asia and sub-Saharan Africa. The share of the population with internet access in developing countries is low, and is only about 20 per cent in the least developed countries. Large variations are seen from country to country.2

Figur 2.2 Internet access in 2019

Kilde: wearesocial.com

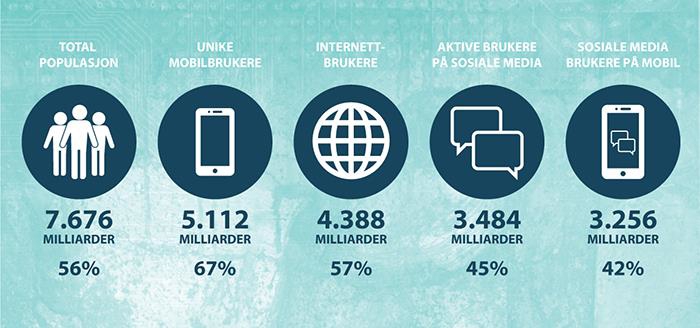

Figur 2.3 Global access and use, 2019

Kilde: wearesocial.com

While much of the world’s population lacks affordable internet access, many of those who do have access use only a fraction of the potential it presents. The digital divide corresponds to – and reinforces – existing inequalities in wealth, opportunity, education and health. Many people who lack secure and affordable digital access belong to groups that are already marginalised or living in poor or rural areas.

At the end of 2018, more than 5.1 billion people subscribed to mobile communications services, an increase of 1 billion in four years.3 Eighty-eight per cent of the world’s population lived in areas with mobile broadband coverage. Access is unevenly distributed around the world. Ninety-two per cent of the Southeast Asian population lived in areas with such coverage, while in sub-Saharan Africa the corresponding figure was only 54 per cent.4

In addition to mobile internet, fibre-based fixed internet connections are available in many coastal areas of developing countries, but it is often expensive and thus only accessible to a small portion of the population. Intensive efforts by SpaceX, OneWeb and others are under way to expand internet access in developing countries using satellites in low earth orbit.5

Until full internet coverage becomes achievable in practice, there are technological solutions offering basic information and services to rural areas in sub-Saharan Africa. The “Internet Lite” project is a good Norwegian example of this (Box 2.1).

Digital inclusion and access to information for all

Norway supports the Basic Internet Foundation through the Vision 2030 initiative. The foundation, a collaboration between Kjeller Innovation and the University of Oslo, uses digitalisation to provide access to information as a basis for inclusion and strengthening of the rights of individuals and communities.

The Basic Internet Foundation works to provide free access to the information internet, or “Internet Lite”, and its overall objective is to promote digital inclusion. The foundation has developed a solution in which digital content requiring a large amount of bandwidth (such as video content) is filtered out, while “lighter” content (text and images) is made openly available. The foundation estimates that one person’s paid use of content requiring greater bandwidth can fund free access to “lighter” information content for dozens of users.

The foundation has developed inexpensive Wi-Fi hotspot systems for installation in villages that lack internet coverage, providing a very affordable “Internet Lite” to village populations in collaboration with local mobile communications operators. The systems are now being tested in Tanzania and the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

2.1.2 Regulation

Internet access is an essential factor for digital transformation to occur, but is not enough on its own. A strong analogue foundation is also required in the form of laws, regulations and institutions that make it possible to establish digital services and regulate the flow of data in a way that safeguards societal security, personal privacy and the private sector. Norwegian cooperation with developing countries to strengthen the competence and capacity of their public institutions therefore provides important support to realise the potential inherent in digitalisation.

A sound business and regulatory environment is crucial for a well-functioning private sector, which in turn is a prerequisite for job creation, economic growth, poverty reduction and government revenue generation. Assisting countries to establish stable and conducive framework conditions for business operations, investments and economic growth is a priority for the Government.

Regulation of the telecommunications market in Myanmar

The effects of Myanmar’s new Telecommunications Law of 20141 and the granting of licences to operators show the transformative power of updated regulations. The law introduced competition and created a stable framework that extends to foreign mobile operator development. It also lowered SIM card prices from USD 150 in 2013 to just USD 1.50 in 2015.2 The proportion of the population with mobile internet access in Myanmar jumped from 4.2 per cent at the end of 2013 to 23.3 per cent at the end of 2015. Government authorities also required operators to ensure that 10 million of the new subscribers were women. From the start, the authorities imposed coverage requirements on mobile operators, demanding high-quality coverage for mobile services and infrastructure even in new and previously inaccessible areas outside cities. As a result, the country’s citizens and businesses have been able to skip the analogue telephony stage. Five years after the introduction of a regulated telecommunications market, 75 per cent of the population are mobile internet users.3 In April 2018, the country established a dedicated fund for mobile telecommunications development in rural areas.4

1 https://www.jonesday.com/en/insights/2013/12/myanmars-new-telecommunications-law

2 GSMA Intelligence, market data for Myanmar, January 2019.

3 GSMA Intelligence, market data for Myanmar, October 2019.

4 http://www.iicom.org/regions/asia-pacific/item/myanmar-starts-universal-service-fund

2.1.3 Digital competence

Digital competence may be defined as the ability to use digital devices to access, manage, understand, integrate, communicate, evaluate and generate information safely and effectively.6 Such skills are also commonly referred to as ICT literacy, information literacy and media literacy.

Both traditional reading skills and digital skills are needed to utilise and take advantage of the benefits of digital tools. Inadequate reading skills lead not only to basic language weakness but also to an inability to put modern technology to practical use.7 Even with a smartphone in hand, reading skills are needed to understand the device’s user interface, read what is on the screen and use the keyboard. For many people, the lack of a secondary language is a further obstacle to using the internet or a mobile device. More than 55 per cent of all websites have English, Chinese or Spanish as their main language.8 In regions with a high degree of illiteracy, mobile internet use is generally low. Women and marginalised groups are overrepresented among those lacking digital skills. In the poorest countries, the most important barrier to mobile internet use for men and women alike is a lack of reading skills and digital literacy.9

In sub-Saharan Africa, 54 per cent of the population have mobile internet access, but for various reasons only 24 per cent use it.10 In Myanmar, which has a mobile network coverage rate of 75 per cent, Facebook accounts for almost all data traffic. According to a 2018 report by the Pathways to Prosperity Commission,11 almost all of the people in a group of developing countries (Kenya, Tanzania, Uganda, Nigeria, Bangladesh, Pakistan and India) have used a telephone to call someone at one time or another, but only about half have sent an SMS and only 30 per cent have used the internet. Digital exclusion is less and less a matter of users versus non-users and more about how and how often the technology is used. Access alone is therefore not sufficient – digital skills must also be developed locally.

There is a growing mismatch between the knowledge, skills and abilities of young people entering the workplace and the knowledge, skills and abilities being sought by employers. At the same time, the number of young people seeking to join the labour market is steadily rising. This illustrates the importance of access to education that builds digital competence.

2.1.4 Inclusion of marginalised groups

The most vulnerable groups are also the most difficult to reach. Digital technology may have a wider range than local, geographically defined projects. The opportunities offered by new technology can be used to reach marginalised groups and achieve the objective of leaving no one behind. The challenge is that the most marginalised groups are often those with the least access to digital tools and the internet, or even to electricity. Additionally traditionally excluded groups such as women and the rural poor, are the least effective internet users. Globally, 23 per cent fewer women than men are mobile internet users, and in South Asia the figure is 57 per cent.12

The barriers preventing marginalised groups from using digital technology are numerous and complex. Telephony and mobile data costs, lack of relevant content, and security concerns are major barriers to mobile device ownership and mobile internet use. For many girls and women, negative social norms and strong social controls pose additional barriers to digital participation. If these barriers are removed, the potential is great.

Digital solutions can for example help to increase the participation in society, employment, social contact and political engagement among disabled people. According to the World Bank, 15 per cent of the world’s population have some form of disability.13 Digital tools allow those who fall outside the ordinary labour market to create their own workplace and invest in their own futures. Girls and women can gain access to education and work digitally even if, for various reasons, they must spend most of their time at home. Digital tools to report sexual abuse, harassment at school and slave-like conditions for children are other examples of the benefits of digitalisation for marginalised groups. In humanitarian crises, drones can distribute emergency aid and money can be transferred digitally to areas inaccessible to emergency personnel. Mobile technology can give marginalised groups access to savings accounts, credit and insurance. New digital business models providing market presence can be of great importance to ethnic minorities or others living in outlying areas.

Digitalisation in banking and finance has especially great potential to help a wide range of people. Digitalisation has made it possible to include people who otherwise might be invisible in public registries such as those documenting birth, death, marriage, business ownership, property ownership and school enrolment. If we manage to guide digitalisation towards including people who would otherwise be left out, we can promote a digital transformation of society with unbridled potential for development, democratisation and the protection of human rights.

Figur 2.4 SINTEF’s test of screening technology for hearing impairment in Tanzania is a good example.

Kilde: Photo: Tone Øderud, SINTEF

Digitalisation of public services can provide a major boost to people living in extreme poverty and others who have been discriminated against or marginalised. Equal treatment can only be achieved if state and local authorities demonstrate equal commitment in all areas, including those where religious, ethnic and political minorities live. Otherwise, digitalisation could actually reinforce discriminatory and corrupt social mechanisms.

The risk of digital exclusion must be considered in all digitalisation efforts. While the effects of having a digital identity are generally inclusive, it may be difficult to obtain biometric or other digital information from certain groups in the population. In some countries, ethnic minorities have been excluded from digital population registries.14 More than 75 per cent of the world’s stateless people are members of a minority group.15

2.2 Digital security – a prerequisite for development

The role of the internet in national economies, security, growth and development opportunities is large and expanding. At the same time, our increasing dependence on digital solutions gives rise to new vulnerabilities. The digital space opens societies to new and serious cross-border threats from both state and non-state actors. Such challenges are discussed in more detail in the International Cyber Strategy for Norway (2017) and the white paper Global security challenges in Norway’s foreign policy (Meld. St. 37 (2014–2015)).

Defence against digital threats is growing in importance. But defence alone does not create security. It is also necessary to address the underlying causes of the threats and to weigh potential countermeasures against the many benefits and opportunities that the digital space provides. We must strike the right balance between security and openness. A well-functioning digital space requires both. In addition to maintaining digital security, it is crucial to protect democratic values and the rights of individuals.

The authorities in countries where democracy is weak can use data and internet surveillance to strengthen control rather than to increase inclusion and transparency. Digital surveillance tools can be used against political opponents, journalists and critical voices in civil society. Digital platforms can be misused to spread hate and disinformation or to incite violent extremism. There have also been disturbing examples of personal data being harvested, covertly and on a vast scale, for use in political and social manipulation.

Digital security challenges are something all countries have in common, but they are harder to address in countries with weak societal structures as well as countries in conflict or in vulnerable regions. If the populations of developing countries are to seize the opportunities of digitalisation, it is important to strengthen the countries’ ability to address digital challenges and threats. Areas to focus on include institutional development, legislation, education and training, and knowledge and technology transfer.