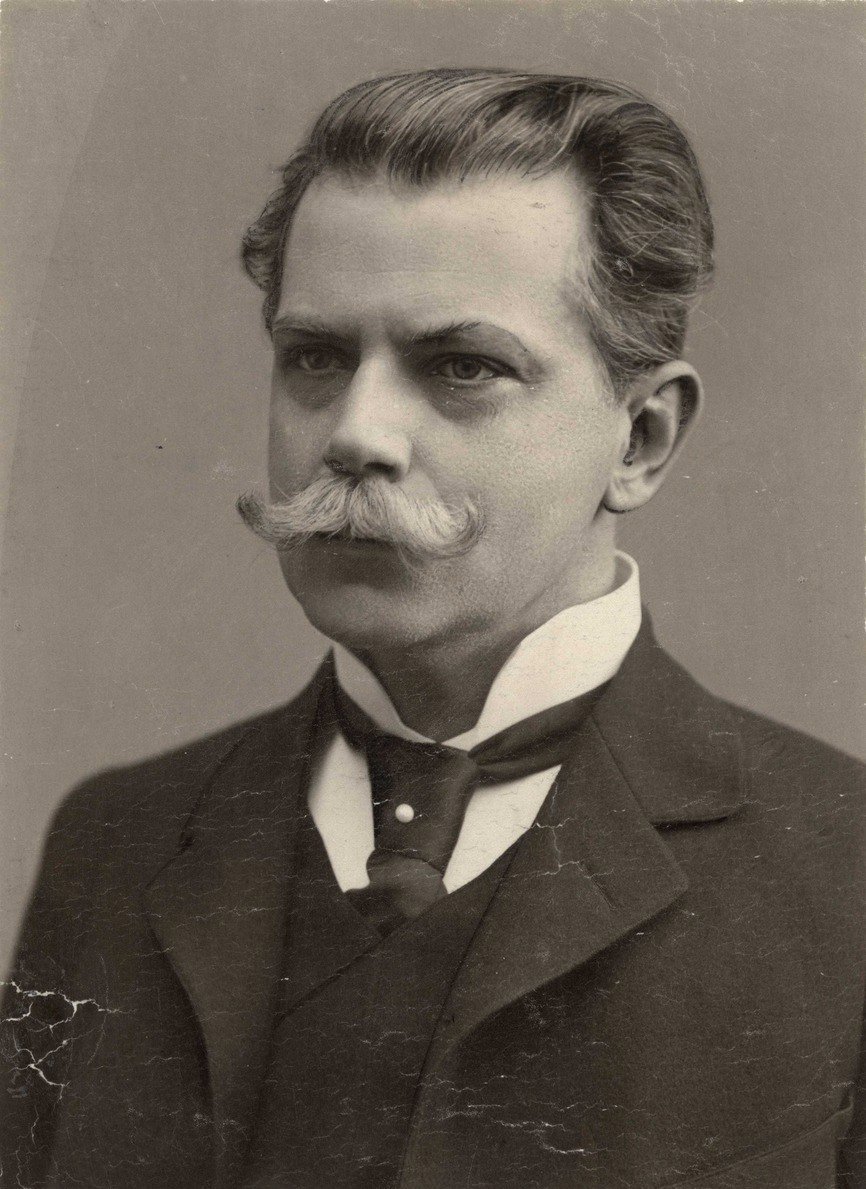

Sigurd Ibsen

Norwegian Prime Minister in Stockholm 1903 - 1905

Article | Last updated: 10/04/2012

Sigurd Ibsen was lawyer, author and politician.

(Photo: Oslo Museum).

Councillor of State 21 April 1902-22 October 1903, member of the Norwegian Council of State Division in Stockholm.

Norwegian Prime Minister in Stockholm 22 October 1903-11 March 1905.

Born in Christiania (Oslo) 23 December 1859, son of author Henrik Ibsen (1828-1906) and Suzannah Daae Thoresen (1836-1914).

Married at Aulestad in Østre Gausdal 1892 to Bergliot Bjørnson (1869-1953), daughter of author Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson (1832-1910) and Karoline Reimers (1835-1934).

Deceased in Lausanne, Switzerland 14 April 1930. Buried at Vår Frelsers gravlund (Our Saviour Cemetery) in Oslo.

The first 30 years of his life Sigurd Ibsen spent mainly abroad with his parents, primarily in Italy and Germany. His possibilities to meet Norwegians of his age were thus scarce, and his Norwegian language was without any local character. To those who did not know him, he might therefore appear impersonal. On the other hand he early on acquired a thorough knowledge of European politics and culture, which gave him an independence of opinion that his contemporaries in Norway might only achieve at a far more mature age. His Italian and German were fluent, and he had a good command also of French, English and Swedish.

Ibsen studied law in Munich and Rome, in 1882 achieving his Italian doctor’s degree with a thesis on the upper house in the system of representative government.

In these years Ibsen appears to have been in doubt about which career to chose. Despite his Italian doctorate, his lack of a Norwegian university degree barred him from becoming a Norwegian civil servant and – as it looked – choosing a Norwegian academic career. After some time at the trade and consular office of the Norwegian Ministry of the Interior, he chose to accept a Swedish invitation to enter the foreign service. The Norwegian Government immediately granted him an attaché scholarship.

In 1885 Ibsen became unpaid attaché at the Swedish-Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Stockholm. He then served at the Swedish-Norwegian embassy and consulate-general in Washington DC 1886-1888, and at the embassy in Vienna 1888-1889.

However, cooperation between Ibsen and his Swedish superiors was not perfect, as Ibsen to a large degree saw himself as a Norwegian and did not entertain the same admiration for Swedish governance as did other young Norwegians in the foreign service. After his years in Washington DC Ibsen said he did not want to return to the Ministry in Stockholm, and he allowed himself to write in Norwegian when preparing his Swedish superior’s reports to Stockholm. After having learned that he could not expect promotion by his superiors in Stockholm, he chose to leave the service. He gave an account for this in a series of articles in the Norwegian daily Dagbladet in January 1890. This caused strong reactions from the Swedish side.

Ibsen now came to live as a writer for the next decade, mainly in Kristiania.

In Norway Ibsen had joined the circle around the quarterly Nyt Tidsskrift, in the 1880’s issued by Ernst Sars and Olaf Skavlan. Here he in 1883-1884 had published articles on the historic development of the notion of the state. His writings revealed a comprehensive knowledge of constitutional and sociological literature, an exceptionally clear mode of expression and an impartial attitude.

His experiences from the Swedish-Norwegian diplomatic service made Ibsen engage in the efforts to achieve a separate Norwegian foreign service, a view strongly marked by the Liberal Party’s philosophy. He accused Norwegian politicians for their weakness towards Sweden, and for their lack of ability to uphold Norway’s position in the union. In his thesis Unionen (”The Union”), which was distributed in large numbers in 1891, he laid a theoretical foundation for a policy to give Norway its own foreign service – fully aware that this might break the union with Sweden. In 1897 Ibsen founded the quarterly Ringeren, which had as its aim to work for a new Norwegian foreign policy.

In these years Ibsen lived mainly in Kristiania, where he attempted to make his family – which had grown to the number of five – subsist by his writings. After Ibsen in 1894 had proposed that the University of Kristiania should have a chair in sociology, the Storting granted means to cover lectures in the discipline. In the winter of 1896-1897 Ibsen gave a well-attended lecture series in sociology. However, the University concluded not to offer him the chair, and decades should pass before sociology had a separate chair at the University of Oslo.

The quarterly Ringeren was one of Ibsen’s more successful efforts in the 1890’s. He linked up with leading writers as his father-in-law Bjørnson and Ernst Sars, which made the publication reach a level of quality rarely seen in Norway. Among his own lectures published in the quarterly was one where Ibsen broke with the Liberal Party and argued against Norway becoming a republic should the union with Sweden be dissolved. He said a continued monarchy would better express the dominant political tendency of the time, and argued that it would also be an advantage in the foreign policy.

In 1899 the trade and consular office of the Ministry of the Interior was expanded into a department of trade, shipping and foreign affairs, and Ibsen was appointed director general and chief of the department. Ibsen had in the 1890’s not been too happy that the issue of a separate consular service had been held out as the most important issue in the efforts for independence. To him there were national reasons why Norway as quickly as possible should become fully independent from the Swedish Ministry of Foreign Affairs, and he saw the isolated struggle for a separate consular service as postponing this.

As chief of the new department in the Ministry of the Interior Ibsen now had to handle the issue of a separate Norwegian consular service under the joint Swedish-Norwegian foreign policy leadership. His study of the issue, which came in 1901, came to represent a decisive turning-point. The study disposed of the claim that such an arrangement was impossible. Following a Swedish initiative new negotiations were now opened, and Ibsen was appointed member of the Swedish-Norwegian commission to further study the matter. The commission’s unanimous recommendations came in the summer of 1902, largely supporting Ibsen’s views. These recommendations now laid the basis for the last rounds of negotiations on the consular issue.

Ibsen’s leading role in this process led to his appointment as councillor of state in the Liberal Government that was reconstructed with Otto A. Blehr as prime minister in April 1902. Blehr allegedly offered him the post as Norwegian prime minister in Stockholm, but as Ole A. Qvam wanted this post Ibsen allegedly accepted to be one of the two other members of the Norwegian Council of State Division in Stockholm.

Despite the fact that he was seen in Norway as well as in Sweden to be the actual representative of Norway’s negotiating policy in union issues, Ibsen still did not come to have a dominant role in the negotiations taking place between four Norwegian and four Swedish ministers in 1902-1903.

In late 1903 Ibsen’s strong profile in public life came to lead to the breaking up of Blehr’s Government. Ibsen was worried at Defence Minister Georg Stang’s rigid attitude on how a possible conflict with Sweden should be handled. Ibsen’s line was that the union should be dissolved in a peaceful way, and he claimed that Blehr now would have to choose between Stang and himself. The Government’s fall led to a decline in the support for the Liberal Party, which in turn made Ibsen rather unpopular in the party. This again contributed to Ibsen withdrawing his resignation, to be appointed Norwegian prime minister in Stockholm in Francis Hagerup’s Second Government.

Ibsen’s main motive for continuing in the Government was to work for a settlement in the issue of a separate consular service, and as the Prime Minister in Stockholm he would be able to lead negotiations on the Norwegian side. However, the atmosphere in Sweden was now changing to less positive to a compromise, while Ibsen came to maintain Norwegian points of view stronger than Liberals at home had expected. Ibsen lost his grip on the matter, and when Hagerup’s Government was forced to leave in March 1905, Ibsen found himself to be on the outside of main events.

The dissolution of the Swedish-Norwegian union was carried out and defended along the consistent line maintained by Ibsen as late as in February 1905, when he was more set than most to break the union. His critics claimed however that Ibsen had less radical aims, and that his line of action would not have led to what came to be the result.

It appears that Ibsen in late 1905 turned down an offer to enter Norway’s new foreign service, due to disagreement with Prime Minister Christian Michelsen. The offer was not repeated, and he was neither offered to join the Government anymore. On the other hand Ibsen took no initiative to involve himself in politics or the civil service. After having inherited his father’s fortune and copyrights he no longer had any economic reason to do so.

I 1906 Ibsen became member of the Court of Arbitration in Haag, besides working as a writer. His main work is the essay collection Menneskelig kvintessens (”Human Quintessence”) from 1911. He also wrote the futuristic drama Robert Frank (1914) and the comedy Erindringens Tempel (”Temple of Remembrance”) (1917).

As most of his income came from Germany, Ibsen’s economy deteriorated during the First World War. He sold his house at Slemdal in Aker (Oslo) and settled abroad. In the 1920’s he bought a villa near Gossensass in South Tyrol (Italy), where he had been living as a child. Here, in Villa Ibsen, he lived until his death in April 1930.

Source:

Norsk Biografisk Leksikon